Tacloban

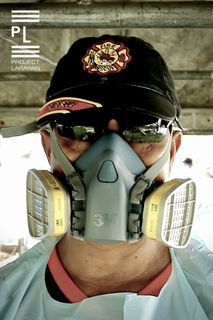

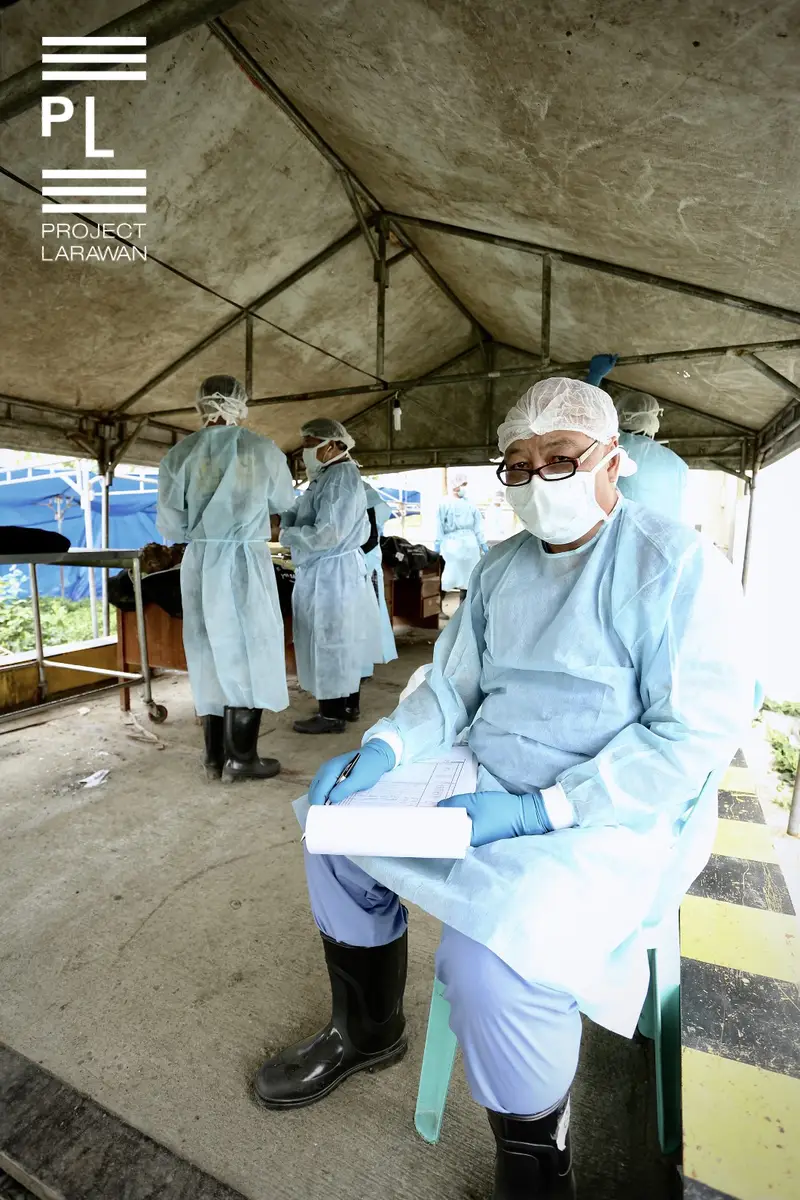

I went through my Tacloban files in search of a photo that really captured how Yolanda affected me. The photo that stuck out was an image of National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) workers "processing" the yet to be identified bodies in Suhi. A body bag would be opened; the cadaver would be checked to see if a finger print could be taken. If not, the teeth would be checked. If identification by teeth was not possible, then the femur would be sawn off and kept for record purposes and identification at a later date.

Bodies were processed one after the other, but more body bags arrived and the piles never seemed to be reduced. The dead literally stared at me. And the stench stayed. Several years later, I still remember the very strong odor of death.

When you walk into a catastrophic situation, where countless families have been displaced, where desperation and despair abound and streets reek of death under the rubble, you will be moved.

You want to console. You want to offer solace and support. You want to help in any way you can. Not because you are Mother Theresa personified. Because how can you not be anything but affected? Something is stirred inside you. A calamity devalues all of us.

Kinship is in our DNA. It is only natural to want to respond to the human condition. It is compassion that makes us human.

And if we lose that compassion, that very thing that defines us as a species, then what are we anyway? We merely take up space, consume oxygen, and start hard-headedly insisting on a lower 2,000 casualty count, thinking perhaps it diminishes the tragedy. If humanity is merely reduced to a statistic, then that speaks volumes of the kind of people we have become. We have lost our capacity to feel, desensitized most likely by countless hours on a console, racking up points in video games.

This collection, however, is made up more of stories of hope. Of men being compassionate. Of the better sides of our imperfect selves.

There is a Filipino word for that. Malasakit.