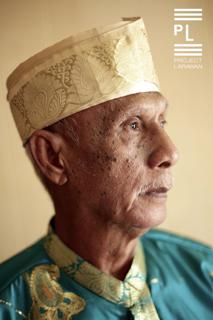

Lupah Sug / Sulu

I watched her sleep in peace.

The deep blue evening sky above her unfolded endlessly, mirrored by the calm seas surrounding her below. In the stillness of night, Sulu was beyond beautiful in all her quiet majesty and mystery, casting a subtle spell that for a moment brought me seven centuries past, when Arab missionaries first laid eyes on her, and introduced her people -- the proud Tausug -- to Islam.

Since the 12th century, Muslim traders and missionaries from Arabia and Persia had arrived in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago through Sumatra, Indonesia. In 1380, more than a century before the Spaniards introduced Christianity in Cebu, Arab missionary Karim ul-Mahkdum came and fortified Islam among the first Muslim settlers in Sulu, laying the foundation for the political rule of his successor, Rajah Baguinda, from 1390 to 1460.

Years later, Sayyid Abu Bakr Abirin, an Arab explorer and religious scholar from Johor in present-day Malaysia, married Baguinda’s daughter and settled in Sulu, establishing himself as the first ruler of the Sultanate of Sulu, which reigned through a succession of descendants until 1915. Throughout the country’s colonial history, Sulu’s sons and daughters would bow only to Allah, even as others would come to subdue them, with swords and crosses, pistols and rifles. The conquerors would come and go, fail and turn away in shameful defeat. Sulu would be left unconquered, her people unbowed.

During Martial Law, the Philippine army battled with the Moro National Liberation Front forces that had laid siege on Jolo that February in 1974. In the crossfire, civilian homes and business establishments were burned to the ground, families rendered homeless, charred corpses left in the streets under the sun. A generation later, embers still burn in the minds of those who remember, glowing in their eyes when they speak of what was lost in that fire.The town has since been rebuilt, with modest low-rise buildings replacing older structures that were destroyed.

Now, on this moonless night in February, on the eve of hearts, 40 years after the great fire that torched the town, I stood on the balcony of a house in Camp Bud Datu, the Mountain of Kings, home to the final resting place and shrine of Rajah Baguinda. Before me, the view was like a dream. Between earth and sky, the silhouette of a mosque that survived the burning of Jolo, Masjid Tulay, stood quietly with its round dome and crescent moon at the center of four towering pillars. Below, in the capital town, a patchwork of rusty tin roofs sheltered sleeping families where children dreamt of better days. Beyond the town, on one side were the lush mountain forests and sleeping volcanoes, and on the other side, the pristine coasts facing the open seas and the haven of marine life underneath.

The vision made me sigh. I turned to go into my room to collect my recent journeys in writing. And then it happened. Suddenly, loud explosions broke the silence and ripped through the evening’s reverie. My heart skipped a beat. The Marine soldiers guarding below instinctively reached for their guns as they stood on alert and looked in all directions to find where the blasts were coming from. The surrounding darkness suddenly breathed danger.

But it turned out to be a false alarm. Just above the town, we witnessed a rare and dazzling display of fireworks. Even Jolo now celebrated Valentine’s Day with a bang. After confirmation by radio and a repeated survey of the surroundings, the night was cleared. There were no enemies tonight. Not yet, at least. I had asked earlier if the extremist Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), hiding in the sloping forests to the east towards Patikul, could lay siege on this camp on a mountain. Not likely, I’d been somewhat assured. There were stations and posts below. Dogs would be barking. And besides, if such an attempt were to happen, we would have the upper hand of defending from higher ground. For now it was just a celebration of sorts by the few who could still afford fireworks. The soldiers sighed in relief and lowered their weapons. I sat down and took a breath. Now, the spell had been broken. The sound of fireworks had exposed a pervasive underlying fear of war and death. Such was life in Sulu.

Though weary and full from my travels, I felt restless now and could not sleep, partly from the strong homegrown Robusta coffee I’d had in the late afternoon, but more from this unmistakable sense of danger that lurked beneath the shroud of night. Not just for myself.I was just passing through.The locals, on the other hand, lived witht his every day of their lives.

In the past, I had traveled to other remote islands in the country. But it was only here that I traveled like a captive, escorted everywhere by a team of Philippine National Police in some places, and the Marines in others. Recently, I had spent time in Patikul, in another military camp. I’d visited the home of a Datu, a kilometer or so from the Abu Sayyaf camp, along a beautiful beach. There I felt the urge to go for a swim, but could not. It did not feel right to take leisure while uniformed escorts were risking their own lives to protect mine. Kidnapping was a reality here, as were encounters with -- and beheadings by -- the dreaded ASG.

One time, we had planned on going to the village of Parang to visit the mosque there. But the mayor had radioed, “Maraming baril sa daan.”(There are many guns on the road). And itineraries had to change. Just like that. Instead, I found myself at a party to which the Provincial Director was invited. One of his Special Action Forces police was married to a local girl. It was inspiring to see how they carried their ancient culture in sacred ceremonies beginning with the Pagpassal, a practice of purification for both bride and groom before the actual marriage. During the wedding rites, both groom and bride wore colorful traditional costumes and jewelry that included gold and pearl rings, as a promise of prosperity. I had made awkward attempts to meet and talk to the locals while being escorted around, and my meanderings somehow led me to some of the finest traditional weavers of Sulu. Aside from seeing the iconic pis siyabit, I was awestruck by incredible tapestries of colors and patterns on cloth that spread and extended across walls and ceilings. One was a visual narrative of how the world and people were created. And then in a neighboring barangay, I met a young village woman who created intricate embroideries and sold her work to pay for tuition, went to school for a semester, and then stopped schooling to work again to earn enough to pay for the next semester.

And now I was brought here, to this mountain fortress of Camp Bud Datu. The camp had been used by the military as a center and stronghold in promoting order in the area. Amidst a decades-long struggle for Bangsamoro faith and self-determination, addressing poverty has turned out to be essential to establishing peace, while establishing peace has proven vital for economic growth and livelihood to flourish. In the meantime, while peace negotiations forged on and gained ground, the extremist Abu Sayyaf remained at large -- and active. And so, here, fireworks could easily be mistaken for gunfire.

The morning sun started to rise. Sulu began to awaken. As dawn broke and the skies began to light up, the ancient voice of prayer soared through the birthing of a new day, while children went off to school. I looked out from the balcony again, sleepless yet dreaming, for this land of unfulfilled promise to find her peace.

February 2013