Tawi-Tawi

Tawi-Tawi derives its name from jaui, which means far away. To city-centric urban folk, it is an outlier, lying at the southern fringes of the archipelago. Yet there is nothing marginal about it.

It is a place unto its own, an alluring blue world crowned by cumulus fleece and defined by the currents and ocean movement—where mangroves and seaweed farms emerge in the middle of the sea, where islets and sandbars change form and shape with the rise and fall of the tide, where receding waters announce the urgency of an immediate return home, lest one risks being stuck in the shallows.

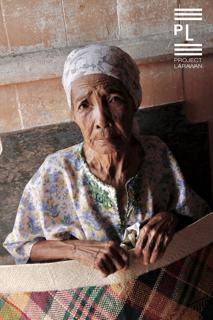

A province on stilts, villages teeter still at the edge of the land while wooded areas within remain untouched. The seafaring and nomadic Badjao and Sama still keep to the waters, refusing to settle inland where space abounds. Its people are of the sea, living off its bounty—fishing and culturing seaweed. If modern social measures are to be used, Tawi-Tawi can be deemed impoverished. Yet, nobody goes hungry. Nature provides.

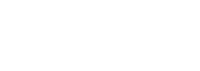

The scattering of islands plays host to a multitude of cultural and archaeological gems. Roads are non-existent in Sitangkai, a village of footbridges built on a reef, where small boats traverse canals teeming with vendors on vessels hawking their merchandise. Engraved coral stone markers are concealed in Panglima Sugala’s ancient burial grounds. The Boloboc caves yield ancient relics pointing to a settlement dating back 9,000 years. Sibutu is home to Kaban-Kaban, a watering hole believed to have healing properties, and upholds a fine tradition of boatbuilding. The four remaining original pillars of the first mosque stand tall and still prevail on Simunul Island. Performances of pre-Islamic, animistic healing rituals by the Sama are permitted only in a Lumah Maheyah in Tabawan. In Tandubas, women deftly weave pandan leaves into tepo or mats, effectively projecting their lives in their handiwork.

As a visitor to Tawi-Tawi, I was in a constant state of bewilderment—whether knifing through murky lagoons in a high-speed boat or following constricted wooden catwalks in seaside communities where corners lead to dead ends. I could’ve gotten lost here.

Islam is the foremost faith, introduced by Sheik Karimul Mahkdum, an Arab missionary, in the 14th century, almost 150 years before the arrival of Magellan. Devotees flock to Tawi-Tawi all the way from Jolo, Basilan, and mainland Mindanao to ascend the abrupt Bud Bongao and pray at the tombs of Arab missionaries on its peak. The pilgrimage was meaningful even to me, a Christian.

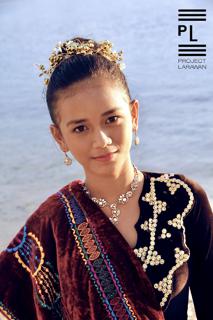

People of diverse beliefs co-exist with each other, weary of the strife that prevails in neighboring environs. Tawi-Tawi is a safe haven; tolerance is the creed, and peace dwells in people’s hearts. This harmony, hopefully, will spread throughout a troubled region in dire need of normalcy and healing.

Sapa-Sapa, Kaban-Kaban, Sanga-Sanga—words in Tawi-Tawi are raised to the second power for emphasis. Superlatives are based on repetition. Vowing to return while in the throes of my departure, finally, it all became clear. The sojourn, like these native words, must be repeated.

Once is simply not enough.

March 2012