Around Lake Sebu

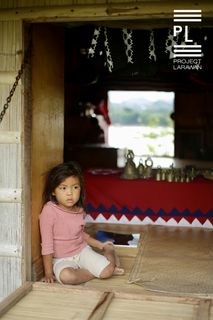

A postcard-perfect idyll of clusters of huts on stilts, restrained carabao grazing close to the water’s edge, or the lonely silhouette of a paddler gliding over the fluid plane, Lake Sebu is often touted as the established home of the Tboli and the centre of Tboli culture.

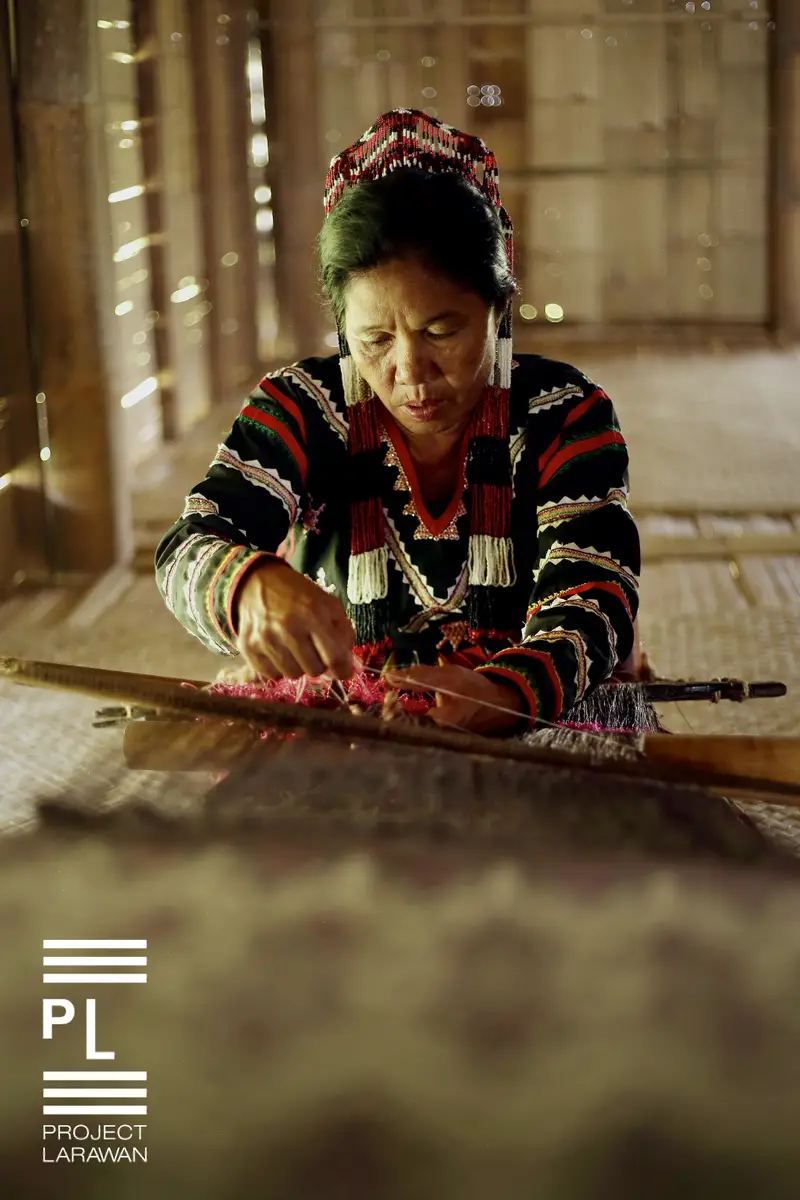

For 600 years, the Tboli have lived there and their culture and craft—weaving and metalwork primarily—have flourished. The Tboli are found everywhere around the lake, whether on the roadside or in the Saturday markets where they display wares for sale. They are hard to miss. And if the colorful garb is overlooked, the jingling of bells heralds their arrival.

The Tboli are of the lake and land. And the lake and land are theirs. Or, were.

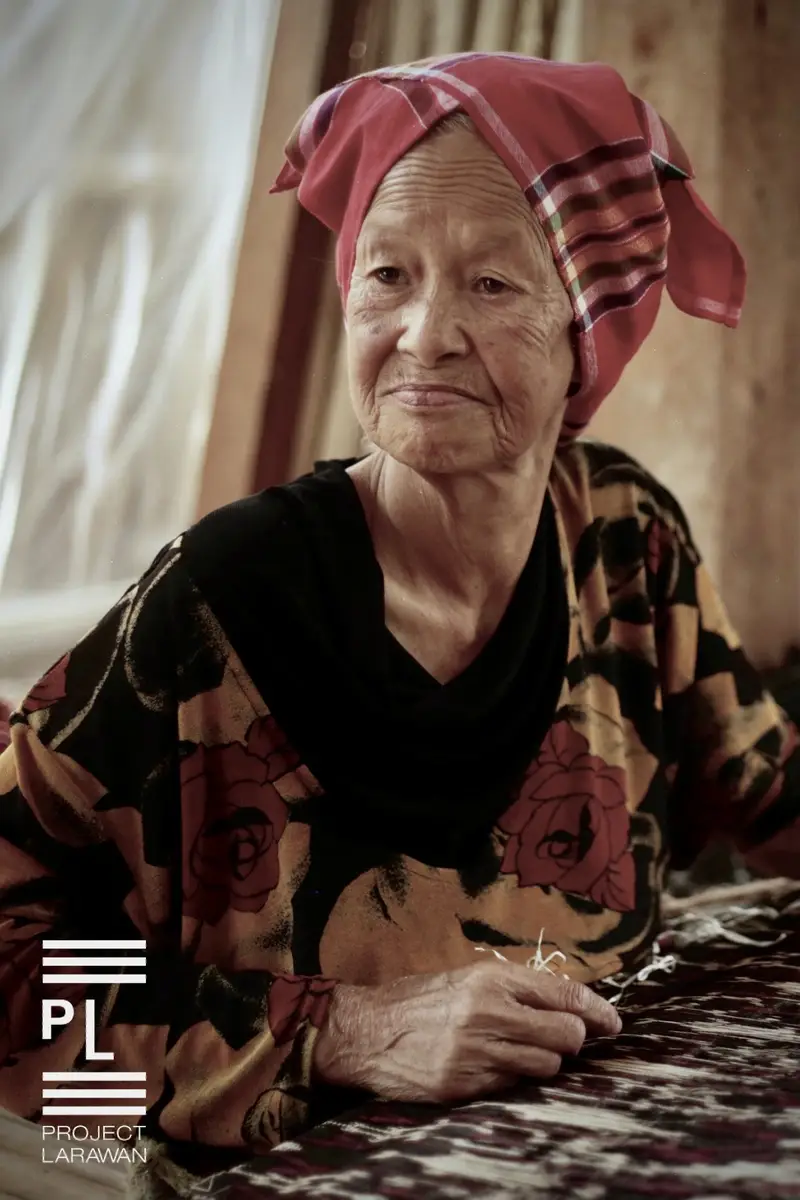

“The encroachment started in the 1950s,” says Maria Todi, an NCCA Gawad Gamaba awardee in 2017 for her initiatives in cultural preservation of Tboli traditions. “Migrants from Luzon and Visayas, particularly from Bicol and Iloilo, arrived in trickles. Because they were generally friendly and not aggressive, the locals coexisted with them. Gradually, control over our ancestral lands was lost as the settlers came armed, not with guns, but with titles.”

The Tboli had no notion of private land ownership, and many have been defrauded out of their ancestral domains in the absence or lack of formal titles to their traditional claims. The Tboli who are by nature non–confrontational, often leave to avoid conflict. And in the times that legal cases are filed to settle disputes, private property laws are not on their side.

Resorts and guesthouses, which serve tilapia prepared in a myriad of ways, line the lakeshore to cater to tourists. Fish pens, formed by the placements of bamboo spokes, break the glassy surface of the magnificent, tranquil pond, appearing as crossword puzzles from above subdividing the lake in numerous sections. The culturing of tilapia has proliferated that the once blue colored lake has turned green from pollution caused by the excessive amount of feed being dispensed, eventually compelling the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to introduce plankton to address the deteriorating condition.

“The lake was part of our ancestral domain. The fishing ground belonged to everyone. Anyone can just throw a net or a line into the lake. Anyone can fish. Or swim. Business interests have now prevailed, depriving the Tboli of what was once communal. Now it is exclusive,” Maria Todi laments. “Values have changed. Mindsets have changed. Commercialization has taken root. The remaining Tboli who still own modest shares of land eventually give in and sell to the highest bidder, seduced by the astronomical prices the properties command.”

“Killing me softly. That’s how I consider it,” Maria Todi, whose School of Living Tradition sits in a spot which overlooks the lake, says.